Alt title: Since everyone asks, here’s what I do with all my free time

I’ve always believed in the importance of documentation, particularly when it comes to one’s own life. Memory tends to be unreliable and it’s nice to have something your future self to look back upon.

In particular, I’ve always romanticized the idea of being someone that journals regularly. Unfortunately, I lack the discipline and to some degree, the know-how. In the past when I would force myself to do so, I found it difficult to discern what was important enough to write down, proceeding to recount the most uninteresting facts and eventually hardly ever looking back on what I had written. It’s the same reason why I always found note-taking in class generally unhelpful and why I had a hard time identifying as a writer for many years, or even as a person who remotely enjoyed writing. In theory, writing about your own life should be the easiest thing to do.

I also own multiple cameras from different times in my life when I’ve gotten really into photography. Recently however, I’ve been neglecting my current camera in part out of sheer laziness and in part because I’ve just been “busy with life.” I find that the intent to document, regardless of whether that’s with a film camera or a phone, can have a distancing effect; rather than actively participating and savoring the moment, the individual becomes an observer preoccupied with discerning what’s worth documenting, or alternatively, becomes the person at concerts who for some reason has to film the entire thing. Recent studies on the relationship between memory recall and media usage confirm this phenomenon, suggesting as Andrew Gregory writes in TIME, that “the act of externalizing their experience — that is, reproducing it in any form — that seemed to make them lose something of the original experience.”

So instead, I collect stuff in boxes, a reproduction-free form of documentation involving minimal curatorial efforts. Inside, each object represents a singular moment from a particular phase of my life. My friend fittingly calls hers her '“ephemeral” box, “ephemeral” from the Greek ephemeros, meaning “lasting only one day.”

I started this practice years ago after one day, perhaps during a particularly severe wildfire season in Southern California, contemplating the question: if your house was on fire and you could only take one item with you (assuming all living members of the household are already safe), what would you take? Put simply, what among your personal belongings is truly irreplaceable?

I liked the idea of having all the most treasured possessions in one easily transportable container, ready to go in the event of an emergency. And with how things are going these days, it seems increasingly necessary to be prepared. For my first box, l had chosen an empty green and purple greeting card container. By the time I was 18, it was filled with with years of mixtapes, birthday cards, photos and friendship bracelets.

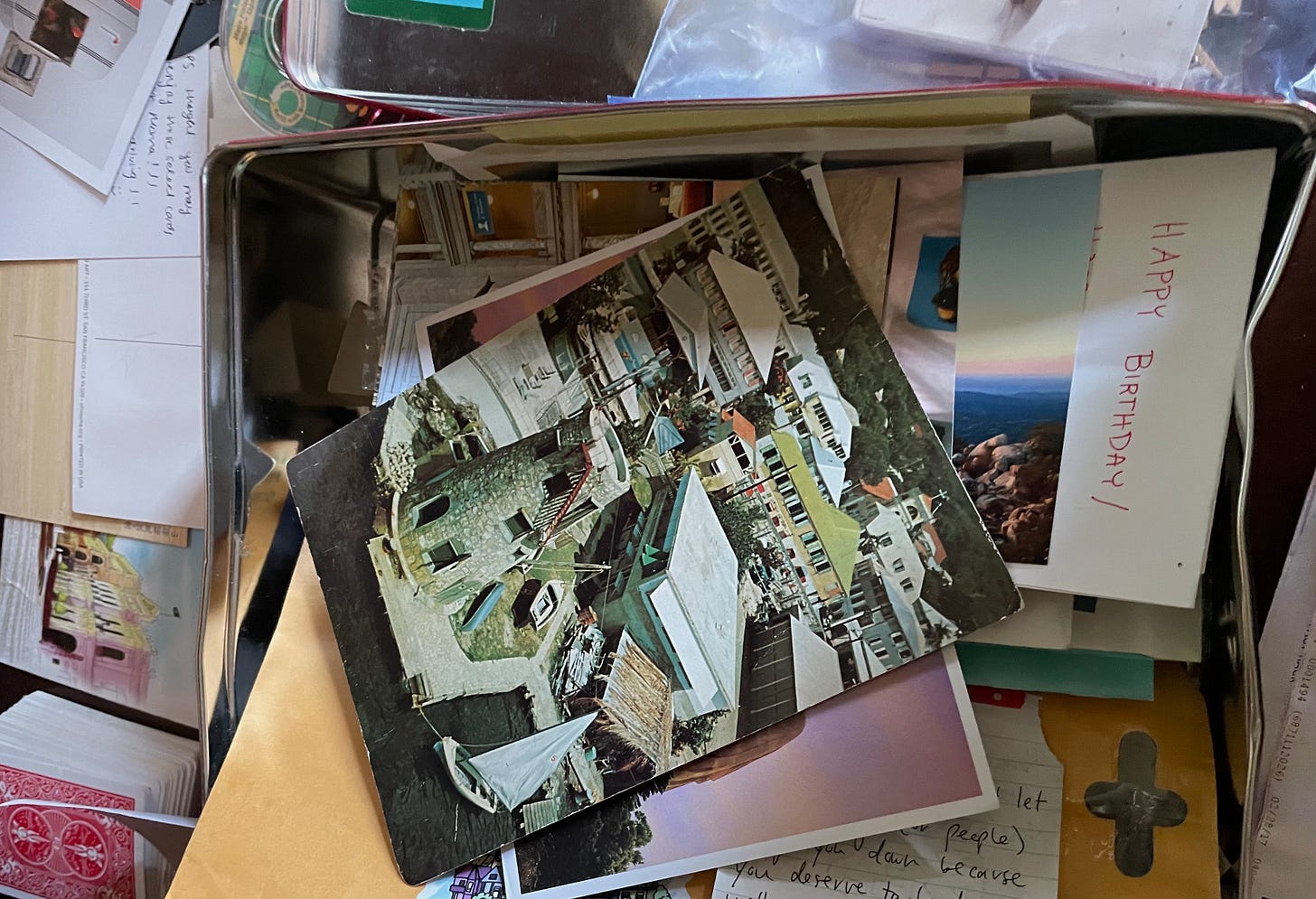

When I went off college, I found a new and bigger box to fill: a shiny red cookie tin now bent so out of shape that it needs packing tape on all four sides to prevent its contents from falling out. Whenever I obtained a physical memento of something that had happened in my life, I would throw it in the box. Like its predecessor, many of its contents were sentimental — polaroids of my first apartment, letters, photos of and with people I love(d), postcards from places I traveled to and have yet to go — but a lot of it wasn’t: ticket stubs from movies I have zero recollection of seeing, an advertisement for a Lil B exhibit at BAMPFA, part of a (clean) Chipotle bag with a short piece on the importance of optimism I liked.

In this case, I prefer the role of the collector, la collectionneuse, because unlike words on a page, these objects do not inherently hold meaning; you are free to create (or abstain from creating) your own personal signification. As a result, even the best-hidden diary cannot guarantee the level of privacy that an unprotected box of semi-random shit offers. What, after all, is someone other than myself and the friend who “gifted” it to me supposed to make of an obscene print of Thanos (yes you read that correctly) that they might find inside mine? The lack of intrinsic meaning is also what allows one to look upon bad memories without necessarily revisiting the pain once associated with them, which might otherwise be passionately elucidated through a detailed journal account written in the heat of the moment. Petty conflicts fade away from the domain of memory and as for actual losses, I can look at a photo where I’m holding someone who’s no longer in my life and appreciate how happy we looked, and probably genuinely felt, right then and there.

However, this year it has become clear that I have far too much stuff and for the last six months, I've made it a goal to Marie Kondo my entire life. First, it was my closet, a laborious several months long process of weeding through some truly questionable pieces I had accumulated over the years while trying to establish a personal style. Then my book collection, the bathroom I share with my sister, and my boxes.

Rediscovering stuff that you had forgotten about is truly one of life’s smallest and greatest pleasures. Among the chaos, I found many things that seemed like they didn’t belong, whether it was because I had thrown them in in the haste of moving or because they just weren’t important to me anymore. But now that they had been preserved for so long, it felt weird to simply throw them away. What are we to do with memories that cease to be meaningful?

It occurred to me that the medium of collage is most analogous to the ephemeral container. Artist David Hockney, best known for his pastel-colored painting of a Los Angeles backyard with pool A Bigger Splash (1967) which, by no fault of the artist, now unfortunately culturally occupies the same spaces as Matisse’s Blue Nudes or the like, began experimenting with photography and creating collages with the pictures he had taken after years of staunch rejection of the former as an artistic medium. On collage and seeing, he said:

“From that first day, I was exhilarated … I realized that this sort of picture came closer to how we actually see, which is to say, not all at once but rather in discrete, separate glimpses, which we then build up into our continuous experience of the world … There are a hundred separate looks across time from which I synthesize my living impression of you. And this is wonderful.”

In How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy (a book with a lot of interesting bits on philosophy, organizing, and contemporary art, in which I first came across this discussion of Hockney’s collage works), author Jenny Odell continues:

“… the eye roams across the scene, dwelling in small details and trying to add it all up. This process forces us to notice our own ‘construction’ of every scene that we perceive as living beings in a living world. In other words [Pearblossom Highway, 11-18th April 1986] is a collage not so much because Hockney had an aesthetic fondness for collage, but because something like collage is at the heart of the unstable and highly personal process of perception.”

Hockney, David. Pearblossom Highway, 11-18th April 1986 (1986).

Objects in ephemeral containers likewise comprise “discrete, separate glimpses” of “our continuous experience of the world.” The artist dictates how they are collectively perceived. So one Saturday night, I decided make a collage of discarded memories, solely from materials inside my box. I don’t really consider myself an artist but it also honestly seemed like a fun, low-stakes creative exercise.

And indeed, there’s something to be said of the act of physically stripping images, particularly deeply personal ones, from their prior contexts, of reconstructing their meaning through that divorce and via their spatial arrangement with other objects that have just undergone the same process. In the end to a stranger, a shoe can be just that, a shoe. I will know it’s mine, but in time maybe I’ll forget what it was next to in that photo, where I was and what I was doing when I took it, because I’ve decided that those things are no longer important for me to remember.

Good read!

I've been getting around my own historical inability to journal by trying to write about someone important to me for at least a minute every day, and hoping that other interesting things will come out if I think of people I love. I've definitely struggled a bit with the desire to document things. I usually forget to take pictures, but whenever I look back on old pictures I'm glad I have them, which makes me want to take pictures more. But since I don't want to miss out on the experience by indiscriminately documenting it, the urge to discern kicks in, and then I start thinking about what will look best on instagram, which makes me feel shallow. I'm trying to compromise by finding moments where it feels natural to take a picture and sticking to those moments, regardless of how they look or what goes uncaptured. I'm really concerned these days about the question of what to do with memories that have lost their meaning. Lack of time and lots of distance make meaningful memories major elements of some of my most important relationships. I worry that in focusing my attention on the future and accomplishing goals and taking action, I may have lost connection with important pieces of the past. I want to believe I can regain meaning in memories that have been dulled by time, but I'm afraid I've lost access to ways of feeling about things by neglecting to think of them and connect them to my present. Maybe it's one of those things where you're supposed to learn how to let go, but I really don't want to. I want my past to give meaning to my present, but that's hard when it's the past's meaning that I lack.